Piloting the use of the ComPAS style protocol

Although a proven treatment for malnutrition exists, less than 1 in 5 acutely malnourished children receive it. A better system can ensure every child receives the care they need.

In 2022, wasting, or acute malnutrition, threatened an estimated 45 million children under five worldwide, leading to the deaths of approximately two million children annually.1 An effective treatment has existed for decades: a daily dose of ready-to-use therapeutic food, or RUTF, (a fortified, peanut-based paste) given to children at health clinics. Despite its proven effectiveness, this solution to child malnutrition is hindered by a broken and inefficient system, reaching only 20% of the children who need it.

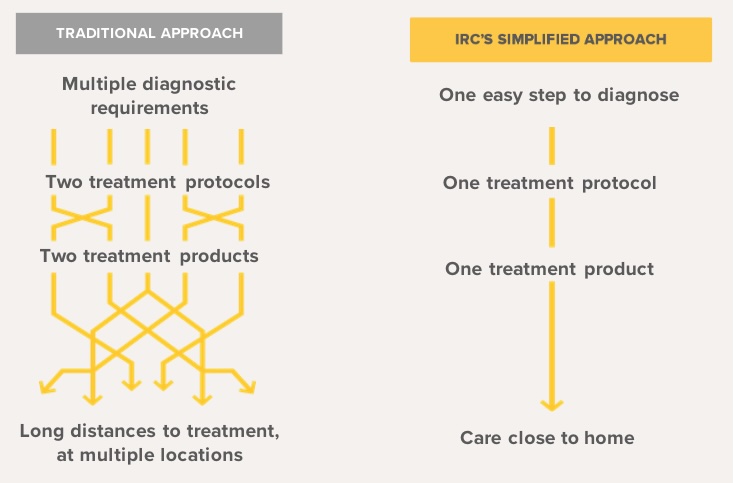

For years, malnourished children have been divided into two categories, moderate and severe. Treatment for each is provided through programs run by different UN agencies, using separate products and supply chains. This complexity is medically unnecessary, limits scale, and drives up costs.

The IRC has developed a radically simpler approach, centered around a simplified, combined protocol for treatment. Under this simplified protocol, all malnourished children are treated at the same site with the same product, spreading fixed costs over more patients. By using a single product, we eliminate multiple supply chains. Additionally, simpler diagnostic tools, like Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) tape, allow health workers to treat children in their communities rather than at distant facilities. The results are clear: the simplified protocol is just as effective as the standard protocol, and it's 21% cheaper, as evidenced in theComPAS cluster randomized controlled trial in Kenya and South Sudan.

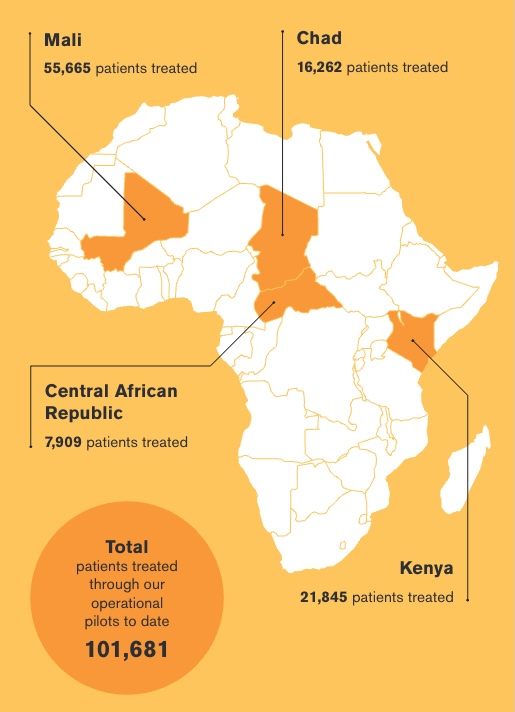

Since 2017, the IRC has piloted the simplified protocol across six countries, treating 101,681 children. Through operational pilots in Mali, Kenya, Chad, and the Central African Republic, we’ve demonstrated the protocol’s effectiveness and cost-efficiency, while also testing various optimizations in real-world settings.

Working closely with health ministries, our operational pilots focus on:

- Implementing the simplified protocol in health facilities and with Community Health Workers (CHWs)

- Measuring patient outcomes

- Analyzing cost and generating data on cost-efficiency to maximize programmatic reach

- Conducting research to refine and optimize treatment delivery

Consistent evidence shows that the simplified protocol is more cost-effective in treating acute malnutrition, offering a scalable solution to reach every child in need.

To learn more about our operational pilots, see the “Project Timeline” below, and explore detailed results from our Mali pilot in the spotlight section.

Spotlight: Mali Operational Pilot

Building on the success of previous pilot programs, our work in Mali offers a closer look at how the simplified protocol can help reach malnutrition treatment at scale.

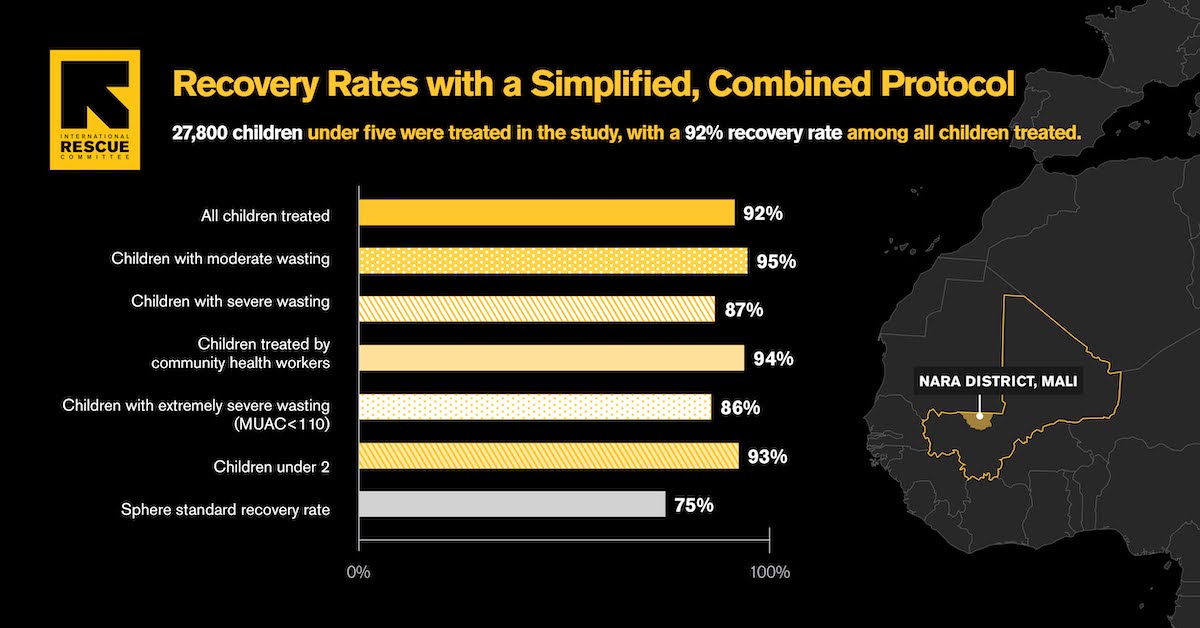

Between December 2018 and April 2024, the IRC conducted a large-scale pilot study in Mali, treating 55,665 children with the simplified protocol. Our findings reveal:

- High Effectiveness: The simplified protocol achieved a 92% overall recovery rate, with an average treatment duration of 40 days and 62 RUTF sachets per child—significantly fewer than standard protocols. Recovery exceeded 85% across all child sub-groups.

- Lower treatment costs: The cost per child treated was lower with simplified protocol than with a standard protocol across every spending category analyzed. Overall, we observed that the total costs per child with SAM treated was 18% less with a simplified versus a standard protocol in the Malian context.2

- Efficacy of CHW Treatment: CHWs achieved a 94% recovery rate, demonstrating effectiveness similar to that of formal health workers.

- Comparable Relapse Rates: Six months post-treatment, 26% of children relapsed, consistent with standard relapse rates (10-70%).

Conducting evidence generation at this scale in routine programmatic settings, outside of clinical trials, allows us to demonstrate the effectiveness of the simplified protocol on a broader scale. Policymakers can use this evidence to evaluate how simplified, decentralized approaches might be implemented in their contexts. Read more in our published article in Nutrients.

To build on these findings, we are conducting a series of focused sub-studies and secondary analyses to identify strategies for reducing costs, improving outcomes, and expanding access to treatment.

Sub-studies and secondary analyses:

Community Health Worker vs. Community Health Center Treatment Quality Study: This study explores differences in treatment adherence between community health worker (CHW) sites and formal health centers to identify potential gaps and improve care delivery.

Visit Frequency & SAM to MAM Transition Study: We are currently assessing how reducing visit frequency and streamlining the transition from severe to moderate acute malnutrition affects program effectiveness.

Distance from Treatment Study: This research examines the impact of distance from treatment centers on nutritional status at admission and treatment outcomes, aiming to determine how far is too far for effective care.

Energy Intake and Growth Study: This study examines the relationship between energy provided and growth outcomes during severe wasting treatment, aiming to optimize nutritional interventions.

Post-Recovery Relapse Study: This study tracked children discharged from a simplified, combined nutrition treatment protocol to assess relapse rates and identify factors influencing sustained recovery.

Response to Treatment Among MUAC 115mm Study: This study tracks children under 5 years old in Mali receiving simplified protocol for severe malnutrition to assess how MUAC, energy intake, and treatment duration affect their recovery. It also examines how factors like age and sex might influence the rate of improvement in MUAC and weight gain.

High-risk MAM: This study assessed data from IRC’s Mali pilot to estimate how many would be considered high-risk by WHO criteria, finding that 95% met those thresholds and suggesting simplified protocols may more effectively target those most in need.

Project Timeline

While our last pilot in Mali finished in April 2024, we’re now analyzing the data. We’re estimating how many children treated with the simplified protocol in Mali would be considered high-risk under WHO criteria. Early results suggest that 95% of children with MUAC <125mm meet at least one WHO risk factor—showing that simplified treatment already targets the most vulnerable. This suggests risk stratification adds little value in these contexts, and that the simplified protocol may be a more practical way to reach those in need. We’re also looking at how distance affects access to care. Caregivers living farther from treatment sites tend to delay care, often arriving when a child is in worse condition. This highlights the need to bring treatment closer to home through community health workers.

The nutrition team performs a secondary analysis of the Mali pilot, exploring the link between energy intake and growth outcomes in the treatment of severe wasting, with the goal of optimizing nutritional interventions. Findings show that children who received more energy at the start of treatment gained weight faster and showed greater overall growth. Defining the healthiest rate of growth remains a critical question for treatment guidelines.

Resource

Publications

- Effectiveness of Acute Malnutrition Treatment at Health Center and Community Levels with a Simplified, Combined Protocol in Mali: An Observational Cohort Study (2022)

- Post-Recovery Relapse of Children Treated with a Simplified, Combined Nutrition Treatment Protocol in Mali: A Prospective Cohort Study (2023)

- Effectiveness of acute malnutrition treatment with a simplified, combined protocol in Central African Republic: An observational cohort study (2024)

- The relationship between energy provided and growth during severe wasting treatment (2024)

- Perceptions of stakeholders on the use of a simplified, combined protocol for treatment of acute malnutrition in Central African Republic (2024)

Donors

- European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO)

- Christina Kirby and Joshua Kulkin Foundation

- Rockefeller Foundation

- Google.org

- Thompson Family Foundation

- World Food Program

- UNICEF

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation